The world needs more vets and farriers - they should be women

This International Women’s Day, Brooke’s Senior Manager of Global Animal Health Dr Shereene Williams takes a look at the gender imbalance within global animal health and explains the impact on animal welfare.

A female vet treats an equine in a Pakistan brick kiln.

Close your eyes and think of a veterinary surgeon or a farrier, who do you see? They might be in wellies, be wearing a checked shirt and a gillet, chaps or maybe a white coat and a stethoscope. Many people will imagine a man.

I’m waiting to see the Vet, are you the nurse? Are you strong enough for that? Can you drive there on your own? Is it safe? These are just a few comments that many female vets and farriers regularly face.

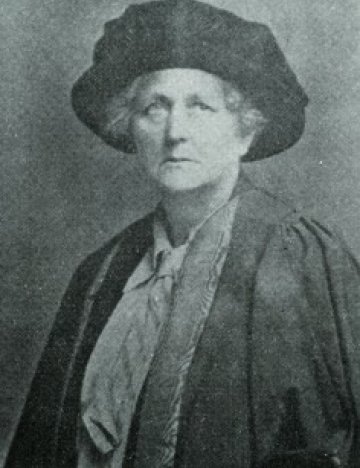

Historically, imagining a man may have been accurate. Dr Aleen Cust was the first female veterinarian to register with the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons in 1922. 100 years later and almost 60% of practising vets in the UK are women. Farriery has also seen an increase in women joining the trade, with the first being registered with the Farrier Registration Council in 1976, who note that just over 3% of the current register is female.

However, such improvements in visibility are not universal.

When we look at the ‘top’ jobs in animal health, just one quarter of the World Organisation for Animal Health delegates, usually a country’s chief veterinary officer, are women. This falls to 11% across Africa and 22% across the Americas.

So while the intake of female veterinary students may equal or even surpass those of male students, in many areas of the world it appears that the top echelons of animal health - such as senior clinicians, policy makers, academia and research - continue to be dominated by men.

What impact do these statistics have on animal welfare?

An estimated two-thirds of poor livestock keepers - approximately 400 million people - are women. Previous Brooke research found that more than 90% of women ranked working equids as most important compared to their other livestock, due to their role in helping women collect water, transport goods to and from market and providing transport for their children to get to school.

So while the intake of female veterinary students may equal or even surpass those of male students, in many areas of the world it appears that the top echelons of animal health...continue to be dominated by men.

Despite this, women are often excluded from animal health training programmes with support focusing on men. A CARE International and ILRI project in Ghana found that while women are the main keepers of chickens and goats, their access to animal health services is very limited. Difficulties in interacting with male vets was noted as the main hindrance to women’s access to care, with animals often dying from preventable diseases as a result. According to Agnes Loriba of CARE, having female vets increases access to animal healthcare for female livestock owners.

We know that the global veterinary sector is facing a critical workforce shortage and chronic under investment. This is particularly felt in the global south. If we compare Pakistan with the UK, Pakistan has half the number of registered veterinarians but almost eight times more livestock animals.

This International Women’s Day, I ask: would having an animal system that is more representative result in improved health and welfare for millions of animals around the world? Can we afford not to unlock the potential in half of the workforce?

Quite simply we need more vets and farriers, and more of them need to be women.

This International Women’s Day, I ask: would having an animal system that is more representative result in improved health and welfare for millions of animals around the world?